Term Essay – Sound, Light, and Health

This paper explores intimately profound experiences in dimensions of sound and light and how they relate to stress. Now that I hear through both ears, I am operating as a different person. I am quietly discovering new ways to hold myself in the world. My stress is less as I have hope for continued improvement. All of my days are different with light’s direct otolaryngeal influence upon my being. I notice this seems true for all of us struggling with a DSM-5 classification for whom a “light doctor” prescribes the right lenses. Slowly I am being released from the prison of being nonverbal, and perhaps even of autism’s biggest claims to my being. Clark Elliott, PhD, a professor of artificial intelligence at DePaul University who suffered traumatic brain injury, describes symptoms very similar to mine with nonverbal autism (183-209). As he recovered his ability to enjoy music, Professor Elliott explains:

“still with my eyes closed, I took my glasses off so I could better relax and just enjoy the music- and the vision immediately disappeared! Instantly, I could no longer hear the magic in the sound. The musical vision became instead only a haunting memory. I was on the outside looking in, through opaque glass.

So I put the glasses back on, with my eyes closed. And … once again I could “hear” my internal, almost ethereal, vision of the music. This was dumbfounding…. With the glasses on, my brain systems converged into a kind of “focus” that allowed for a much broader internal visual canvas on which I could arrange the symbols of my thinking. When I put on my new glasses, the immediate result was that, at least in some ways, my effective working memory expanded, or perhaps my access to it did. This allowed for many times the complexity in my cognitive reasoning. I had much more room in which to work” (222).

Case studies, self-report data, and observational approaches are used to study and treat mental disorders (Hooley. 17-18). A mind-body divide that existed for centuries has only, in the last 100 years, given way to a psychosocial biological model that understands the innate connectedness between mind, body, and environment (Hooley. 48). Within this model, genetic preexisting components are in a dance with environmental influences for better or worse development (69). When behavior injurious to self or others develops, a DSM-5 categorization is often required (159). The labeling is sometimes unrelated to the illness, and a presumption of incompetence may emanate from those who do not know what to do and have never experienced this state. The verbal-based Weschler testing process is a sad testament to how experts in fields connected to autism determine the mental competence of nonverbal persons without concern for the stress it creates for their typically very aware subjects (Eveleth).

Stress is defined as “a negative emotional experience accompanied by predictable biochemical, physiological, cognitive and behavioral changes that are directed either toward altering the stressful event or accommodating for it” (Module 2 Lecture, Slide 4). The stressor is “an external situation, event or condition to which the person reacts with stress,” whether subjectively or objectively defined (5). Already stressed by sensory challenges well-described by Elliott, optimism and sense of mastery are not present. In this circumstance, a DSM-5 diagnosis delivered professionally and without love, as if the subject is unaware, erodes self-esteem and social support (6). Especially where autism is involved, parents often begin to grieve whomever their child will never become (Smyth). The condition’s influence worsens as stress predictably increases.

Walter Cannon’s fight-or-flight response, Taylor’s Tend and Befriend model of stress response, and Selye’s General Adaptation Syndrome describing the biologic stages of alarm, resistance, and exhaustion toward a stressor (9-12) typically become learned accommodation for the many stress-impacted mental and physical maladies a child must endure. When a mind-oriented illness appears to be chronic for patients of any age, recommendations are typically limited to biological treatments such as Seratonin uptake and inhibitor medications (SSRIs) and anti-depressant medications, along with behavioral therapy treatments such as applied behavior analysis, meditation, biofeedback, and neurofeedback. None of these preceding presume competence on the part of a nonverbal autistic, where cognitive behavioral therapy might be more appropriate for experts to see with new eyes. Many learning disorders and forms of dementia are subpar interaction with one’s environment in two stages of life for which biological and behavioral solutions are very limited.

When stress reaches sufficiently high levels, the Diathesis-Stress Model blending of how one sees the world from their limited, stressful perspective, colored by interpretations of what is actually happening, calls for cognitive behavior-like therapy to assist stress reduction and possible escape from depression (Module 3 Lecture, Slides 20-24). This is not possible for those who are considered incompetent, and darkness can deepen, further negatively impacting neuro-transmission in the brain (25). Deeper behavioral disorders can occur.

A healthy immune system protects the body against viruses and bacteria. The biology of stress taxes the immune system, can make it too strong and nonselective in its attack, and can turn on the body in an autoimmune response. A new illness attacking the body enhances the likelihood of autoimmune response (Hooley. 143-144). Chronic stressors can include learning and socialization difficulties, attention deficit issues, obsessive compulsive disorders, challenges holding a job, and financial challenges.

The two primary stress responses are critically tied to the hypocampus. The sympathetic-adrenomedullary (SAM) system begins in the hypothalamus and stimulates the sympathetic nervous system. The hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) system releases precursors resulting in cortisol, which can damage brain cells in the hypocampus (142-143), chromosome-protective telomeres (148), and the feedback loop that protects against inflammation (147). Long-term, stress is considered a cause of biological trigger for depression and anxiety (150-151).

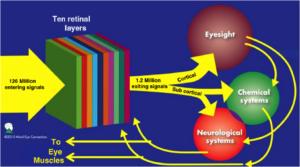

Historically, the retina has been considered as a sensory system limited to sight that feeds information to the brain. Beginning in 1999, the retina has begun to be recognized in science as a “bidirectional neural interface that is an actual part of the central nervous system (CNS)” (Zelinsky. Impact. 411). Combined feedforward and feedback mechanisms are now recognized to exist enabling the retina to be a two-way, noninvasive portal for influence and monitoring of brain and body function and thought process below the conscious level. Direct connections are now understood to exist to brain areas in the cortex, limbic system, cerebellum, midbrain, and brainstem affecting endocrine, respiratory, circulatory, digestive, and musculoskeletal systems. Examples of this are audio-visual sensory disconnects related to ADD and ADHD, schizophrenia, Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy, diabetes, drug addiction, autism, and Alzheimer’s disease. “Changes in retinal function, such as judgments in space and time, can be used as a biomarker for psychiatric disorders” (417-418). “Pupil and eye movement reflex assessments are often used as biomarkers for neurological integrity” (428).

When illness occurs, altered mind and body functions limit processing of the external environment. The mental and physical changes often create symptoms of disrupted brain-body circuitry, and opportunities for treatment and healing through the eyes. Planning, attention and judgment abilities can be improved, in addition to speech, hearing, hormonal and immune functions (412). This can be key to controlling negative effects of cortisol, to reducing stress generally, and to minimizing damage to telomeres.

Among the 126 million light-sensitive receptors, including 120 million rods and 6 million cones in the retinal photoreceptor layers, there are electrical and chemical circuitry pathways with feedforward and feedback systems such that customized lenses as therapeutic instruments in clinical settings can innovatively reduce stress and improve thought.

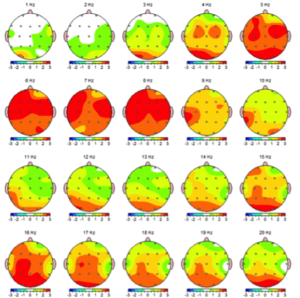

New to science and rich with possibility is the ability of neuro-optometrists to use lenses, filters, and yoked and non-yoked prisms to address the maladies of chemical and electrical systems upset by environmental stress, trauma, and genetic vulnerabilities. These pathways directly flow through the thalamus and hippocampus, impact the SAM and HPA stress response systems, and open a 3rd original and primary diagnostic and treatment modality to brain, body and electrical systems through the retina. The ability to immediately change brain wave function, referenced by Professor Elliott’s direct experience in the beginning of this paper, is reinforced by the case study of electroencephalograms with and without corrective lenses that allowed touching of a bell with eyes closed.

The images of before

and immediately after “corrective lenses” are applied show substantially improved blood flow:

(Zelinsky. Quantitative. 2-5).

Sound and light are the energy of matter. We are reactive instruments in what leading symphony orders from whatever place of peace we can listen. The following diagram shows how we humans are each tied to these the light and, to me, Love.

(Zelinsky. Auditory. 354. Image)

After walking into a restaurant last October, I noticed:

I amplify the energy around me, I notice. When we walked in, I noticed it really more than ever before. What makes me notice it? I think the satiation of sound distinctions is greater. Want to say all of this is significant. I am walking with more awareness of what applies to me and what doesn’t. Powerful loudness was always overwhelming or awareness was squashed as sound was produced. Oasis of wanting to distinguish and I poorly couldn’t. Now I’m easily distinguishing what didn’t even exist before.

I pleasantly say the typer’s biggest challenge is that he doesn’t know what he is missing with sound and sight distinctions and those who work with him don’t know his mental competence is complete and his physical intake is very different.

On November 14, I typed to Dr. Lisa McGuire, my neurologist:

My speech is stronger with eye treatments. All of my hearing is amazingly improved. I wrote about some of it. I’m hopeful I’ll learn to speak soon. The power of eye healing with satisfying ear improvement is untapped as a dramatically immediate, impactful treatment of superior and interior retinal frequency relatedness to brain chemistry, and tapping into a dramatically improved learning process. It uses light as a drug to open functional pathways. I like the new hearing distinctions I never had before.

Within our private experience that works to limit who we see ourselves to be, we stress ourselves to behave consistently with that. When we apply a label, reading another in a particular way, we stress them in addition to whatever other challenges they may have mentally and physically. Work that heals expects wholeness behind whatever illness may exist. Labels should be temporary road signs to helping the circumstance in need of healing, not the diathesis of society’s need to judge.

Works Cited (Links open in new window/tab.)

Elliott, Ph.D. Clark. The Ghost in My Brain. Viking. New York, New York. 2015.

Eveleth, Rose. “The Hidden Potential of Autistic Kids: What intelligence tests might be overlooking when it comes to autism.” Scientific American. November 30, 2011 Web 10 October 2016. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-hidden-potential-of-autistic-kids/

Hooley. Jill M. et al. Abnormal Psychology. Seventeenth Edition. Pearson Education, Inc. Indianapolis. 2017.

Smyth. John. “The Lost Gift.” 2014. Web. July 14, 2018. http://savedbytyping.com/lost-gift-poem-john-smyth/

Zelinsky, OD. Deborah. “Auditory/Visual Integration Assessment and Treatment in Brain Injury Rehabilitation.” Intech. 2014. Web. July 8, 2018. http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/57426.

Zelinsky, OD. Deborah. “Chapter 22. Impact of Retinal Stimulation on Neuromodulation.” Neurophotonics and Brain Mapping. 2017. Web. July 5, 2018. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317312333_Impact_of_Retinal_Stimulation_on_Neuromodulation.

Zelinsky, OD. Deborah and Feinberg. “Quantitative electroencephalograms and neuro-optometry: a case study that explores changes in electrophysiology while wearing therapeutic eyeglasses.” Neurophotonics. V. 4(1). pp. 1-7. Jan-March, 2017. Web. July 8, 2018. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28386574.